| CLAUDIO COSTA | Exhibition 2021 | |

| Magazine |

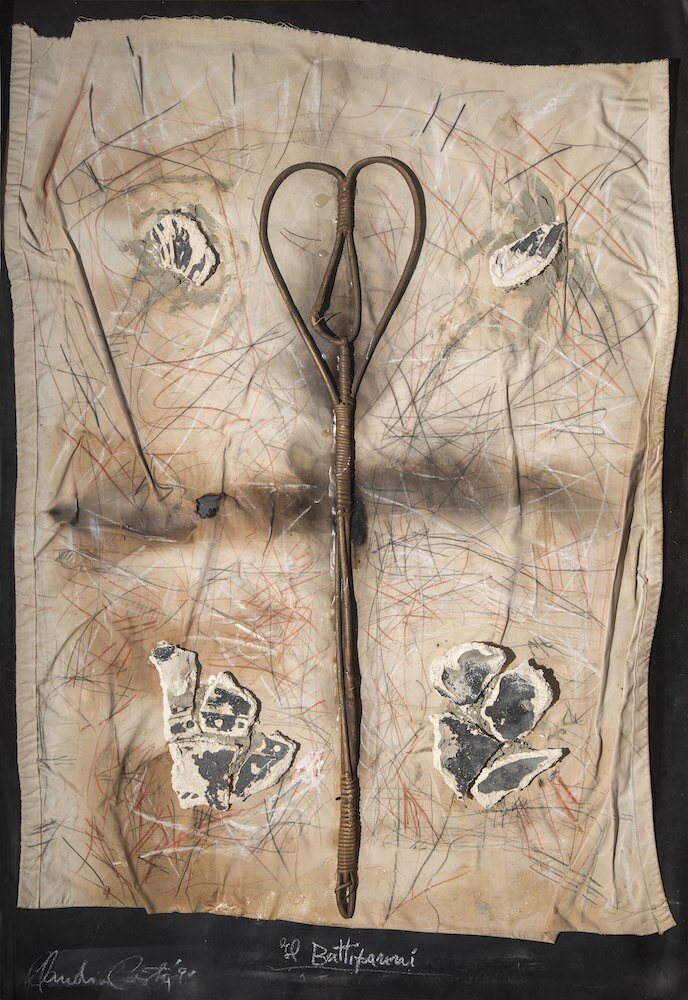

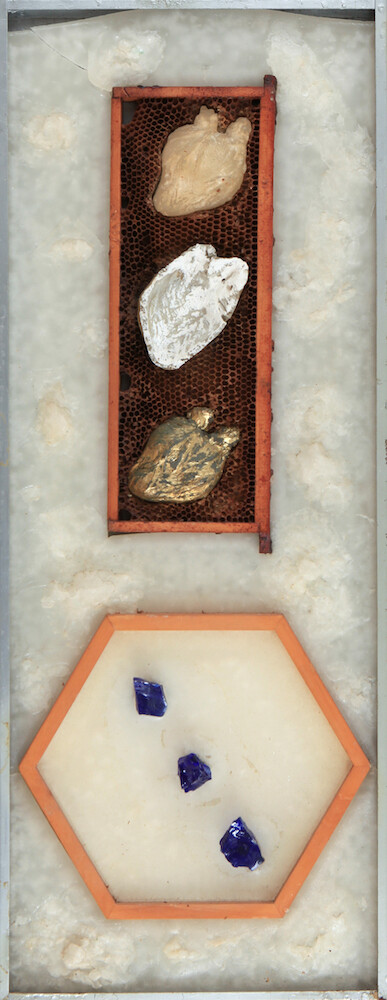

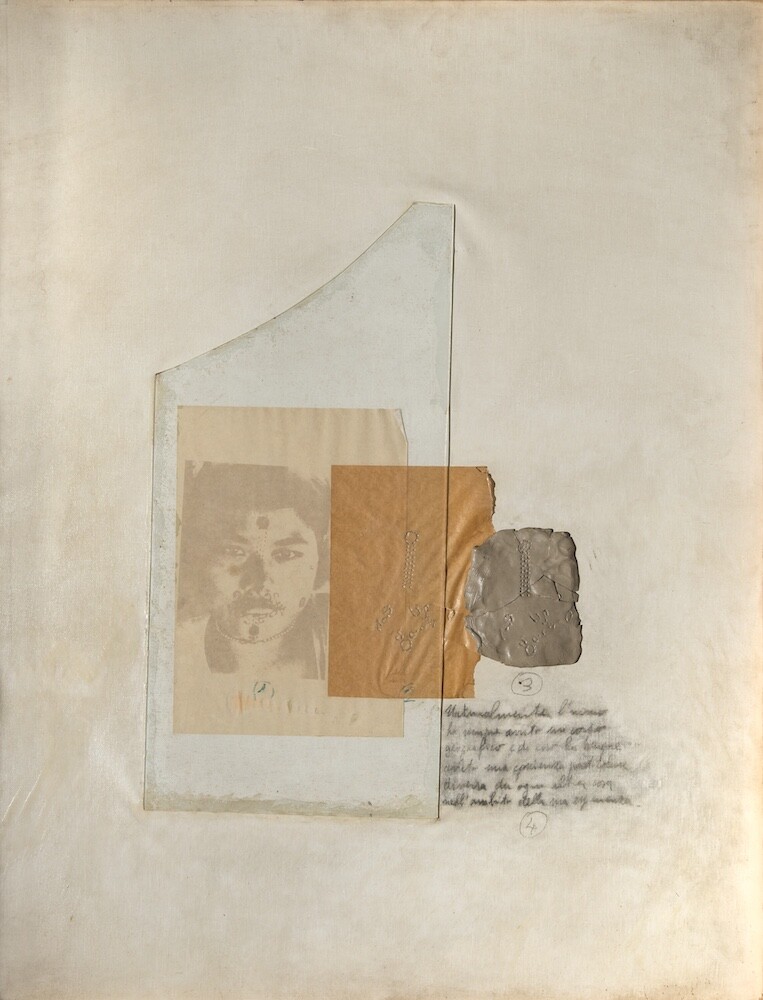

Claudio Costa was born to Italian parents in Tirana, Albania, on 22 June 1942. He spent his childhood in Monleone di Cicagna, in Liguria, and in the ‘50s he went to secondary school (liceo scientifico) in Chiavari. In 1961 he enrolled in the faculty of architecture at the Polytechnic of Milan. Following his great passion for drawing and painting, he began to frequent Enzo Pagani’s Galleria Del Grattacielo, going on to present his first works in Legnano branch. In 1962 he won the “Diomira” award for two drawings and in 1963 he was awarded second prize at the “San Fedele” in Milan. In 1964 he won a scholarship for engraving offered by the French government. He moved to Paris. He worked at S.W. Hayter’s Atelier 17 in Rue Daguerre in Montparnasse where he met Marcel Duchamp. He lived in Passage Rauch 1 near the Bastille. In 1965 he married Anita Zeiro and his daughter Marisol was born. In 1968 he took part in the May ‘68 demonstrations and made the book Mai ’68 Affiches – published by Tchou – along with Alechinsky, Jorn, Bona Pieyre de Mandiargues, Cremonini-Gaudibert, Matta, Dufour-Butor, Milhaud, Ségui and Silva-Cortazar. The works from this period, examples of Pop Art, were displayed in a solo show curated by Eros Bellinelli at Galleria Tonino in Campione d’Italia. On returning to Italy in 1969, he settled down in Rapallo. Numerous critics and artists often stayed in his big house/atelier, including Jean-Christophe Ammann, Bernard Venet, Robert Filliou, Mario and Marisa Merz, Wolf Vostell and Nobuo Sekine. He experimented with materials not specific to art, such as graphite, starch, isinglass, acids, copper sulphate, photocopies and clay. He held his first important one-man show La Vela e Altro at Galleria Bertesca in Genoa, with a catalogue edited by Tommaso Trini and Germano Beringheli, opening the international circuit of contemporary art, from Conceptual Art through Arte Povera to Fluxus. Starting in 1970, his interest focused on palaeontology, a fascinating tool to discover the origin of humankind which would lead him to put on two important solo shows in 1971: Craneologia e altre situazioni at Lucio Amelio’s Modern Art Agency in Naples and Evolution – Involution at Dieter Hacker’s Produzentengalerie in Berlin. He published the book Evoluzione – Involuzione, a scientific text providing the theoretical basis for his anthropological research. A versatile navigator of the soul, in this period he wrote a collection of poems Amore e Disamore which would be published after his death. In 1972 he took part in the “8ème Biennale de Paris. Manifestation internationale des jeunes artistes” at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris in the Italian section curated by Achille Bonito Oliva. 1974 was a year packed with events. He had a solo show at the Neue Galerie – Sammlung Ludwig in Aachen curated by Wolfgang Becker and Astrid Brock. He took part in Spurensicherung. Archäologie und Erinnerung at the Kunstverein in Hamburg curated by Gunter Metken and Uwe Schneede and at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich with Boltanski, Bay, Brodwolf, Lang and i Poirier. He took part in Kunst bleibt Kunst: Project ’74 at the Kunsthalle in Cologne with Boltanski, i Poirer and Nancy Graves, where he exhibited Il Museo dell’Uomo which would then be reproposed as part of the La ricerca dell’identità exhibition curated by Gianfranco Bruno at Palazzo Reale in Milan. Thanks to his meeting the explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl and an intense exchange of correspondence with the Museum of Wellington, he made a series of works inspired by the Maoris of New Zealand. At Galerie Klang in Cologne he displayed Gli occhi dei Maori riflettono i colori latenti della foresta. In summer he journeyed to Morocco to seek uncontaminated cultures; subsequently he published the book Due esercizi di antropologia presented at the solo show of the same name at Piero Cavellini’s Galleria Nuovi Strumenti in Brescia. In 1975 he worked on a series of wooden and glass cabinets containing anthropological objects called Per un inventario delle culture. As Claudio said, “the display case has the ability to immobilize; the glass blocks and fixes the image, separating it from life”. From this idea, with his friend Aurelio Caminati, in Monteghirfo, in the hills of Fontabuona in Liguria, he created the Museo di Antropologia Attiva where the objects of peasant culture – not taken out of their context – become cultural messages, in “a peaceful chaos [that] marks past seasons”. He took part in “documenta 6”, Kassel, presenting Antropologia riseppellita in 1977.

He came up with the idea of “work in regress” in contrast to Joyce’s “work in progress”. He took an interest in alchemy, a phenomenon very close to the origin of things, which leads us back to magic, myth and ritual.

He had a solo show Materiale e Metaforico at Galleria Valsecchi in Milan. He took part in various exhibitions, including Conoscete la magia del verde? at Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna in Portofino and La creazione volgeva alla fine curated by Giorgio Cortenova at Unimedia, Genoa in 1978. He installed the large sculpture Il vulcano addormentato at Museo Vostell in Malpartida de Cáceres in Spain. In 1979, he appeared in Het Mensbeeld in de Europese Kunst na 1945 at the Fundatie Kunsthuis in Amsterdam. In 1981 he took part in Mythos und Ritual in der Kunst der 70er Jahre curated by Erika Billeter at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, then at the Kunstverein in Hamburg with, among others, Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis, Nikolaus Lang, Dennis Oppenheim and i Poirer. He held numerous solo shows in this period. His research on alchemy culminated in Diva bottiglia (per un museo dell’alchimia) which he exhibited in 1986 at the Venice Biennale, in the “Arte e Alchimia” section curated by Arturo Schwarz. He presented Le Macchine Alchemiche at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Palazzo Forti, Verona, curated by Cortenova. A special mention must be made of Costa’s many performances: Controprocesso in Monteghirfo, 1975, Il miele dell’ape d’oro, 1977, Case di fango, 1978, I conigli amano Claudio e altri racconti, 1979, Case di ruggine, 1990, Il nostro avo ci onorò col dono del nero perfetto, 1994 and Arcimboldo evocato, 1994. Starting in the mid-1980s, he worked in a large atelier in the ex-psychiatric hospital in Quarto, Genoa where his research did not prevent him from interacting with the patients as an art therapist. This instinct led him to establish the Istituto per le Materie e Forme Inconsapevoli in 1988 which would become the Museo Attivo delle Forme Inconsapevoli, a space posing no barriers either to the works of professional artists or the patients. In 1989 with Nuovi Strumenti, Brescia, he published Claudio Costa o dell’assedio instancabile del fare with a text by Flaminio Gualdoni. Invited by Claudio Spadoni, he went to Malindi in Kenya to make the sculpture Albero della cuccagna at Giulio Bargellini’s African Dream Village. In 1990 he put on Prehistoire et Anthropologie at Galerie 1990-2000, Paris; Ex hora pre historia, curated by Danilo Eccher at Galleria Il Cenacolo, Trento; and he was invited by Bonito Oliva to “Ubi Fluxus, ibi motus” at the XLIV Venice Biennale. He took part in a series of exhibitions culminating in Europa Africa Versus in 1994 at Galleria Valsecchi, Milan where he exhibited, among other works, Ontologia antologica, a large grained wooden sideboard whose drawers contained the part of the artist in the shadows. It could be described as a Museum of the Unconscious. In 1992 he took part in the Dakar Biennale in Senegal. He returned to Africa on several occasions. Highly sensitized to this primitive culture, he discovered that the outline of Homo Erectus’s brain corresponded perfectly to the perimeter of northern Africa, giving him the idea for the Progetto Skull-Brain Museum – Africa ’95 – which never came to light – in which a museum would be set up in every country he went to in order to symbolically outline the figure in an Infinite Museum of Possibilities and Communications between Europeans and Africans. The concept is expressed in a series of works depicting the map of Africa. The skull and brain were a recurring presence in Costa’s research, from the first Mappe craniche to Credo di essere incinto del mio cervello, from Cervello acido to Calotta cranica Calotta polare, and from Craneologia e altre situazioni to the works on Cuore e cervello. Almost like the alchemic symbol of the Ouroboros, sadly his life ended prematurely on 2 July 1995. Brain aneurysm. The Head That Exploded, 1970.

by Marisol Costa